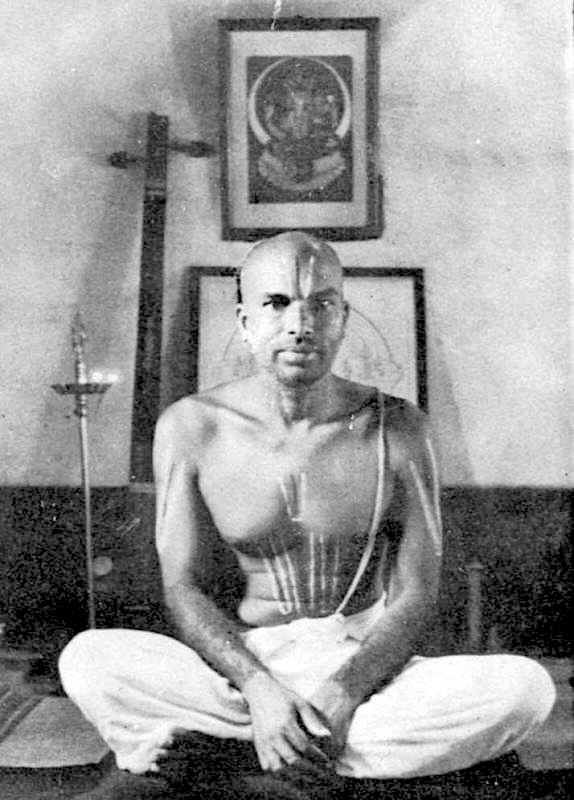

Sriranga Mahaguru

• 1974

It has been rightly observed that all living beings in the world are yearning for happiness and peace and are striving to attain them though the modes of realising the aspirations and the measure of their fulfilment may vary. This is very natural because happiness and peace constitute the very nature of the self. But though all are attempting to reach this natural state those who have actually reached it are rarely to be met with.

Those who are clouded by ignorance make various conjectures on the nature of the self. Some consider the gross body itself as the real self and the gratification of the senses constituting the body as the be-all and end-all of life. "Eat and drink and make merry as long as you live. Why should you worry about a self apart from the body? Who has ever seen it and what proof is there for its existence? Instead of wasting your time in the pursuit of a thing which does not exist at all, squeeze the lemon to the full, drink this life to lees and be done with it," they say. 1

There are others who think that profound questions such as the existence of a self apart from the body are beyond our comprehension. Who can test the well of Truth with the leaky buckets of our minds? The wisdom lies in making this life happy and it is also desirable that we should make others also happy by removing their sorrow.

Of these two classes of men the latter are definitely better than the former but their view of life also is shallow and in a sense they are escapists. They cannot succeed in removing sorrows definitely and absolutely. The happiness conceived by them is subject to limitations. There are some people who make fruitless discussions on the nature of the self without attempting to plunge into its depths. But there are also some brave persons who perform intense sÄdhana driving their senses inwards and reach the immortal Ätman. Those who have thus seen the true self face to face are called á¹á¹£is. The á¹á¹£is may be born in any time or any part of the earth. But history and tradition have recorded that they were born in large numbers and made greatest contributions in the land of BhÄrata.

The á¹á¹£is realised by experience that the Supreme Ätman is the source and substratum of all. It is immutable and is an abode of jñÄna, Änanda, and ÅÄnti, pure and perfect, transcending all limitations. To realise Ätman is the greatest end of life and to disregard it is the greatest folly.

With the supreme Ätman as the nucleus the á¹á¹£is of BhÄrata formed a glorious culture and a civilisation giving an external form to it. Those who follow them reap all the four-fold objects of life -- dharma, artha, kÄma and moká¹£a. Moká¹£a (liberation) is the supreme end of life and dharma is the right principle leading to both material and spiritual happiness. Artha (wealth) and kÄma (sensual pleasure) also may be enjoyed within the bounds of dharma and moká¹£a. 2

But owing to the evil influence of ajñÄna people are apt to forget the significance of this great heritage and go astray. In order to redeem them the Lord manifests himself in the world in the form of incarnations like RÄma and Ká¹á¹£á¹a and also sends from time to time divine messengers serving as his instruments. Such men of God remove the cobwebs of superstition covering the culture and lead men to the sanctum sanctorum of Truth. They also set a pattern of life for people to follow and inspire them with spirituality by the foot- prints left by them on the sands of time 3 even after they have left their mortal coils. The organisation called Aá¹£á¹Äá¹ ga Yoga VijñÄna Mandiram was founded by a MahÄpuruá¹£a coming in the above line and his blessed name was ÅrÄ«raá¹ ga.

ÅrÄ«raá¹ ga was born at a village called Heá¸attÄle in the Mysore District in a family of ÅrÄ«vaiá¹£á¹ava BrÄhmaá¹as, as the son of ÅrÄ« TirumalÄchÄrya and ÅrÄ«matÄ« Rukmiá¹i Ammal on a Friday which was the fourth day in Ká¹á¹£á¹a Paká¹£a of KanyÄ mÄsa in the year PramÄthi (19-9-1913) and attained parandhÄma on the same day and tithi and paká¹£a in the Kumbha mÄsa of the year KÄ«laka (7-3-1919). The life and doings of this remarkable personage did not come to light to the world at large because being in tune with the desire of the Lord he chose to remain as a "fruit behind leaves". Here we attempt to give a brief pen-picture of this man of God and the institution founded by him, for the benefit of those who have an aspiration for the greatest value in life.

The MahÄguru was a house-holder pursuing agriculture as a means of living and led a normal life like others without any ostentation. But behind this unassuming life shone an inexhaustible fountain of spirituality and the greatest qualities of head and heart which inspired veneration in all who came in contact with him. As a revered ÄcÄrya, a great exponent of the BhÄratÄ«ya Culture and Civilisation, as an affectionate and dutiful relative and friend and member of the society and as a humanitarian inspired by unselfish love he had reached the water-mark of greatness though his greatness was known only to a small circle of men who had the fortune to be acquainted with him.

He was an ÄcÄrya of the highest calibre. Our ÅÄstras describe an ÄcÄrya as one who has realised the Truth, who gives a correct of exposition of the ÅÄstras, establishes good conduct and practises what he preaches and ÅrÄ«raá¹ ga MahÄguru fully conformed to this standard [4]. He was a spiritual giant who had risen to the heights of Brahma SamÄdhi and was firmly established in it even when he was working in other states and so saturated was he with spiritual power that when he was possessed of a divine saá¹ kalpa, his touch and sight, a momentary remembrance by him and even the things that he had touched or seen or thought of had the efficacy to awaken slumbering souls to the states of Yoga. He possessed a majestic and well-formed constitution conforming to the description of a Yoga-MÅ«rthy [5], who would be a ÅubhÄÅraya, an auspicious and efficacious object for meditation. His profound and resonant voice rising from the depths had the power to drive away all inertia. A word or two from him and a sight of his face beaming with lustre of pure sattva gave comfort and solace to many afflicted souls.

He was born in a family holding the ÅrÄ«vaiá¹£á¹ava faith and its tradition and code of life were dear to him as he had realised their value. But as a master-yogi with his perfect acquaintance with the high-ways and bye-ways of all the various branches of religion such as the Åaiva and the ÅÄkta. leading to the same goal of Brahma SamÄdhi 4. He had equal love and respect for all of them and the natural MudrÄs of all the gods worshipped in these faiths were seen adorning not only his body but also the bodies of his disciples when they were in meditation, disciples born to different faiths were attracted towards him and he showered his blessing equally on all of them and undertook to lead them to the same heights of BrÄhmÄ« Sthiti. He was a JñÄnÄ« merged in Brahman, a bhakta inspired with divine love and also remained as a Karma YogÄ« serving God with sincerity till his last breath. He had great respect for the saints of the dwaita advaita and visistadvaita schools and had an appreciation for good things in other religions too. He remained unscathed by the fare of bigotism with which the society is consumed and he cautioned his disciples also against the defects of viewing things through coloured glass. He advised the men of different sects to stop mutual mud-slinging and perform sÄdhana in the right path without abusing their time and energy in fruitless discussions. Experiences of the supersensuous state cannot be decided by waging battle of words in the physical plane.

His definition of the term ÄchÄra (right religious conduct) shows how honest and unprejudiced his outlook was: "ÄchÄra does not necessarily mean the religious conduct of such and such a sect living in such and such a country. It means any act which cleanses the mind and enables us to see the Self shining in its pure state."

He did not remain contented with his realisation of Brahman but freely transmitted his knowledge to the qualified disciples out of divine compassion. He tested the praká¹ti of the disciples and taught them according to their aptitude and capability. When once he took up the responsibility of a disciple after divine sanction, he would never leave him until the goal was actually reached. He had boundless affection for his spiritual sons and shed tears of joy when they were found reaping spiritual experiences as expected by him. He did not forsake anybody who came to him sincerely for help in the spiritual field. If a person was found unfit at the time to receive initiation he would ask him to wait patiently and to purify himself in the mean time with good saá¹skÄras.

He was a saá¹ská¹ti puruá¹£a of the highest order replete with JñÄna and VijñÄna as the warp and woof his life and worked with indefatigable energy for the cultural renaissance of humanity. Though he had very little formal education either of the university or of the traditional type he was gifted with the wisdom of understanding the vidyÄs and kalÄs. When men with academic distinction both in the university and traditional fields ran up to him with problems he could solve them within no time. He was a past-master in the knowledge of the mechanism of the body and its working embracing all its fields the gross, the subtle and the spiritual. He did not despise the body but considered it rightly as a temple of God. He also did not condemn the senses but made them as instruments to reach the Lord within and to project His glory without. When projected outside his senses were most active and could grasp even the subtlest things.

Some ignorant people disparage Gá¹hasthÄÅrama as a stage of disqualifying life for JñÄna. But like ancient Sages like Vasiá¹£á¹ha he proved with his own example that even a Gá¹hastha can become a Brahmaniá¹£á¹ha (greatest knower of Brahman). Recognising SannyÄsa as a stage of life in which there is scope for socialisation in JñÄna he had great respect for it, but he also remarked that whereas a SannyÄsÄ« can make a gift of JñÄna only, a gá¹hastha (who has realised Brahman) can make sixteen MahÄdÄnas such as the gift of food and clothing in addition to JñÄnadÄna. He himself was such a MahÄgá¹hastha praised by sages like Manu and his name ÅrÄ«raá¹ ga (the theatre for the goddess of Spiritual wealth and glory to show her graces) also was true to significance.

He was a NÄda Yogi who had listened to "internal sounds" leading to paramÄtman and was also a GÄna Yogi who could bring out the glory of NÄda to the external world and help listeners to soar up to the heights of Yoga. He could understand the psychology of animals and birds and insects and could draw them towards him by mimicry and singing. He was also peerless in physical feats and skills like swimming and diving and climbing trees. He had in his youth vanquished a buffalo that had attacked him accidentally. He was a keen observer of Nature and Nature revealed her secrets to him. His knowledge of plants and medicinal herbs was superb. He had an excellent taste for both SÄhitya (good literature) and SÄhitya (good food), He also excelled in writing pictures. He was endowed with the gift of gab and was a good conversationalist. He knew the art of teaching even extremely difficult subjects in the most effective manner. His speech was interspersed with homely similes and other natural figures and replete with Rasas like humour which could be simple and profound as demanded by the occasion.

He had learnt those sciences and arts sitting at the feet of the Lord who is the teacher of teachers and the Lord of all vidyÄs and KalÄs. Their source and their right use and put them to the best use to which they could be put. He knew how to harness them for Yoga and also for Bhoga unopposed to it. He used his GÄna (ras) as a means of yoga to awaken the KundalinÄ« power. Through the pictorial art also he brought out experiences of the inner world and made it an instrument for teaching. He made use of the knowledge of medicines to cure the diseases of many people, distributing medicines and treating them freely. He did not make use of spiritual power to cure physical ailments as he had reserved them to cut off the worldly bondage. (He cautioned his disciples also against the pursuit of Siddhis (occult powers) which are only obstacles in the way of attaining the greatest Siddhi namely the realisation of Ätman.) With a reverence to the great sages who gave VidyÄs and KalÄs, he offered their fruit at the feet of the Lord.

He had an unparalleled love for the land of BhÄrata not merely because it was his motherland and a land of wealth and beauty but also because it was the land of a wonderful Saá¹ská¹ti and a civilisation bridging earth and heaven. He hated superstition both of the ancient and the modern brand and never compromised with untruth. But he showed with reason and practical experiments that many of the things in our religious customs and traditions which are dubbed as superstitions are products of ripe wisdom. He was a lover of modern science and scientific methods and scientific apparatus also were used by him in expounding great truths. He viewed science as a part of the ÅÄstras as it faithfully explained things as seen in the physical plane and has also bestowed many material comforts upon us. But the root and substratum of all and the real meaning of life and the experience of supreme joy and tranquillity can be attained by yoga only.

The á¹á¹£is have enjoined upon us the performance of sixteen Saá¹skÄras and daily and occasional rites and have declared that they purify the mind and generate JñÄna. But how they do this has not been expounded with necessary details. Those who have blind faith in tradition observe them mechanically and their faith is being shaken by rationalists. In this context the MahÄguru clearly showed with the proofs of reason and experience that taken in the form and spirit given by the á¹á¹£is those Karmas are really efficacious in purifying the mind and bringing enlightenment. Thus he was the redeemer of Karma ÅÄstra as a bridge to JñÄna ÅÄstra.

Even in the midst of his multifarious works regarding our Saá¹ská¹ti he devoted himself to the duties of a householder towards the members of the family and relatives and friends. He was most hospitable to guests and kind to the poor and the needy. But he followed the vow of Aparigraha. He gave bounteously to others but did not receive help from others [note]. He had pleasing manners. His face was wreathed in smiles in entertaining others and whenever there came any calamity or need for service, he would be present there to render his active services in the most modest manner. His disciples and relatives and friends and guests and even other people were helped by him in various ways in times of misery and each one of them declared that he loved him most. Such was the fascination of his wonderful personality. "The elements so mixed in him that Nature might stand up and say to all the World. This was a man not a mere man but a man of god".

He proclaimed that realisation of the self which is eternal and is an ocean of perennial happiness and peace is the chief end of human existence and other objects also can be pursued in consonance with this) and also declared that it was the birthright and prerogative of all human beings. This cannot be attained by mere book-learning but by devotion and the performance of SÄdhana under the guidance of an enlightened man, we should purify ourselves by obtaining good Saá¹skÄras by doing our duties as designed by the seers who had a complete outlook on life. When the vidyÄs and KalÄs and traditions and customs as taught by them are followed we reach the goal of life. This message was the same as that which was given by the Mahará¹£is who framed our culture. But the MahÄguru assimilated all that knowledge and proclaimed them to us in an original and powerful manner in a language befitting our standard. The portrait of the person presented here may strike some readers with wonder. Some may even disbelieve it. Did he really exist or is he merely a product of imagination ? We humbly submit that he was a reality who lived with us in flesh and blood in recent times and influenced the lives of many men. He lives forever in their hearts to inspire them.

To give a concrete shape to the truths that he had realised the MahÄguru founded an institution called Aá¹£á¹Äá¹ ga Yoga VijñÄna Mandiram and also gave it an emblem which is an epitome of all ÅÄstras and KalÄs, a treasurehouse of JñÄna and VijñÄna and the water-mark of art elevating to divinity. The term YogÄbhyÄsa is current in the sense of performing some Äsanas or physical postures and breath exercises called PrÄá¹Ä- yÄma and even acrobats demonstrating wonderful physical feats are called YogÄ«s. This is a disparagement of the term. The Rishis who gave that word to us used it in the sense of the highest state in which the supreme goal of life is realised It is derived from the root 'Yuj' which means 'to unite or to be in the state of tranquillity'-the state of union of JÄ«va and ParamÄtma when all problems are solved and the self enjoys its natural and normal rest. It is also called Sahaja Sthiti and Unmani. In it the mind is yoked to the highest object of life and its other functions come to a stand-still and the self becomes divested of association with sorrow. It also means a balance of the mind and skill in work. A course leading to yoga is also called yoga. Though such explanations are different they all refer to the positive and negative aspects of yoga and the means of attaining it. The stages in attaining the highest state of Yoga are generally enumerated as eightâYama, Niyama, Äsana, PrÄá¹ÄyÄma, PratyÄhÄra, DhyÄna, DhÄraá¹Äand SamÄdhi. The last three of these are most important, (with the omission of the first two stages Yoga is called á¹£aá¸aá¹ ga). VijñÄna is the special science and art of reaching the state of Yoga and coming back from it with a complete understanding of its course. The Mandiram or the mansion for practising it is verily the body. So the MahÄguru very often proclaimed that the term. Aá¹£á¹Äá¹ ga Yoga VijñÄna Mandiram, chiefly applies to the body in which the knowledge of Yoga is practised and attained.

In a secondary sense it refers to an institution with the above object and the Mandiram in this sense was founded on the YijayadaÅamÄ« day of the year Sarvajit (24-10-1947) at Heá¸attÄle near the residence of the MahÄguru and those who were initiated by him were its members. The office was shifted to Mysore in view of the facilities available there and it was decided to conduct the activities of the organisation from three centresâMysore, Bangalore and Basarikatte (Chickmagalore Dt.) and the MahÄguru blessed all of them with his visits.

BhÄratÄ«ya culture has a perennial existence being based upon the eternal principles of the supreme Lord, the Light, guiding all the activities of the universe as its spiritual nucleus. It is a divine tree with Satya as the tap-root and Dharma as the shoots and branches. It yields all the objects of life ending in the attainment of the sweet and sappy fruit of supreme bliss. But unfortunately parasites have grown upon it and are damaging the very tree from which they are drawing sustenance. We have to destroy these overgrowths and rear that tree once again in all its pastine glory. A practice of this culture takes the form of Aá¹£á¹Äá¹ ga Yoga. The organisation Aá¹£á¹Äá¹ ga yoga VijñÄna Mandiram aims as a proper under- standing, appreciation and propagation of this glorious culture.

It is carrying an original research work on the various branches of our culture and civilisation and the fruits of this work are made known to the people under proper conditions according to available facilities. The MahÄguru described its members as ' SÄdhakas, Åodhakas and bodhakas ' according to their aptitudes. Seven years ago the Mandiram bought a building in Mysore in the midst of beautiful surroundings for housing its office and carrying on other activities. The Mysore centre is working from there and the Bangalore and Basarikatte divisions are working in private houses. The organisation got itself registered under the Mysore Societies Registration Act in the year 1968. When the MahÄguru left for parandhÄma, the MahÄmÄtÄ of the Mandiram, ÅrÄ«matÄ« Yijayalaká¹£mÄ«, the Sahadharmiá¹Ä« of the MahÄguru, graciously accepted to become the president of the organisation at the request of its members and has been a source of inspiration to us in carrying on the activities of the Mandiram. In addition to giving spiritual discipline to qualified sÄdhakas the Mandiram is arranging pravÄchanas and publishing profound literature on the various branches of our culture. Members deputed by the Mandiram have represented its views on the above subject in cultural gatherings! It has so far published the following works :

- NÄá¹arÄja, an interpretation

- ÅrÄ«Raá¹ ga GÄ«tÄmá¹ta

- ÅrÄ«Raá¹ ga VachanÄmá¹ta in three parts.

- ÅrÄ«Raá¹ ga MahÄguru

These books have been reviewed and appreciated by eminent scholars in public newspapers and received well by the lovers of culture.

We offer the fruits of all our activities to the Light Supreme through the Mahaguru who is shining in the inmost shrine of of our hearts.

Footnotes

1 yÄvaj jÄ«vet sukhaá¹ jÄ«vet, á¹á¹aá¹ ká¹tvÄ ghá¹taá¹ pibet. (↑)

2 "Artha and KÄma are like mischievous cows which give you kicking when you attempt to milk them. Tie up their legs to the pillar of Dharma on the one side and that of Moká¹£a on the other side. Thus controlled even they yield you Amá¹ta (milk, nectar) in immense measure." (↑)

3 "And departing leave behind them, footprints on the sands of time." -- Longfellow. (↑)

4 ÄtmasÄká¹£ÄtkÄra is the birth-right of every human being. Why don't you fight for that right, O Ye men, just as you fight for the right to vote as soon as you become twenty one years old? Fight for that right with all the fire and strength of your soul." (↑)